Charlie Munger’s $2.7 billion net worth at the time of his death served as a powerful reminder that extraordinary wealth may be amassed in a quiet, meticulous, and nearly surgical manner. Munger, in contrast to the flamboyant tycoons of previous decades, amassed his fortune by staying purposefully grounded and constantly sane rather than by pursuing hazardous ventures or speculative trends. His cooperation with Warren Buffett, perhaps the most famous pair in contemporary capitalism, contributed significantly to his financial philosophy, which had been developed over almost a century.

Buffett and Munger were both born in Omaha, Nebraska, and Munger’s early Midwestern beliefs greatly influenced his eventual perspective on risk, business, and life. Following World War II, he attended Harvard Law School, practiced law and real estate, and then shifted his focus to investing. He had already proven to have a deep capacity to integrate many academic fields into logical investment plans by the time he joined Berkshire Hathaway as vice chairman in 1978. He applied engineering logic, economic intuition, and legal reasoning with equal ease.

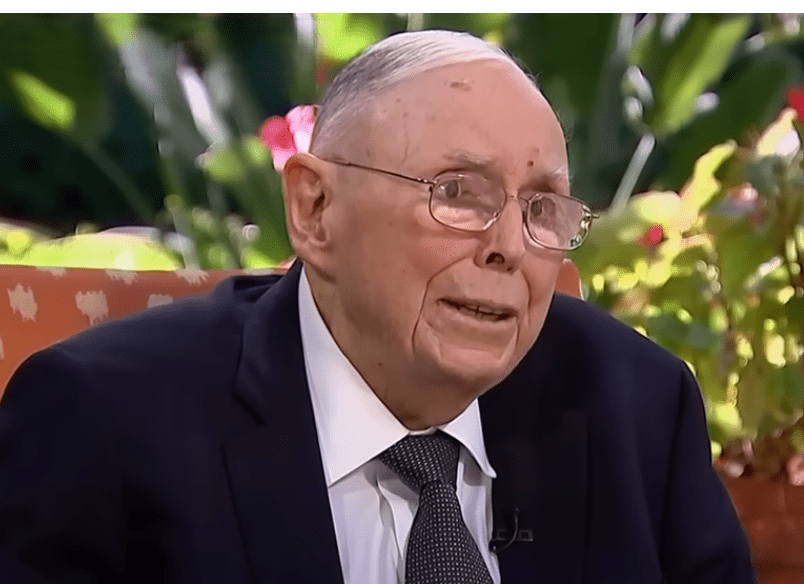

Charlie Munger – Biography and Financial Overview

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Charles Thomas Munger |

| Date of Birth | January 1, 1924 |

| Date of Death | November 28, 2023 (aged 99) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Michigan, Caltech, Harvard Law School |

| Occupations | Lawyer, Investor, Philanthropist, Business Executive |

| Net Worth at Death | $2.7 billion |

| Known For | Vice Chairman, Berkshire Hathaway |

| Military Service | U.S. Army Air Forces, Second Lieutenant, WWII |

| Major Affiliations | Munger Tolles & Olson, Wesco, Daily Journal Corp, Costco |

| Primary Asset Source | Berkshire Hathaway equity stake (3.4%) |

| Reference |

Over the course of their decades-long partnership, Munger and Buffett developed a business strategy that was remarkably obvious in its fundamental principles: avoid needless risk, think long-term, and purchase quality. Munger was more than just a sounding board; he was the driving force behind Berkshire’s shift from low-cost value investment to the purchase of better businesses at reasonable rates. Berkshire’s performance was greatly enhanced by that change, which contributed to an average yearly return of about 20% between 1965 and 2021. Almost 80% of Munger’s entire fortune was made up of his personal interest, which made up 3.4% of Berkshire’s stock.

Munger was wealthy, yet he showed a refreshing disinterest in extravagance. He frequently made jokes about leading a simple life and only eating peanut brittle and Diet Coke. These vices contrasted with his normally austere lifestyle, which was based on self-control and intellectual rigor, even though they were amusing and relatable. Munger believed that true happiness derived from clarity—seeing things as they are and avoiding stupid mistakes—rather than from luxury.

Munger was never one to resort to clichés when asked what he thought was the key to his success and longevity. Rather, he gave remarkably practical advice: never use power, don’t seek temptation, and avoid common mistakes. Echoing Buffett, he famously remarked, “A smart man can go broke in three ways: liquor, ladies, and leverage.” This idea was not just clever; it served as the basis for an approach to investing that was especially advantageous for regular shareholders who couldn’t afford significant losses. Munger made sure Berkshire was extremely efficient and risk-averse, putting long-term sustainability ahead of immediate profits, by refusing to use leverage.

During financial bubbles, when many executives leaned toward reckless credit-fueled expansion, his rigorous approach to debt was particularly prophetic. One of Munger’s most distinctive qualities was his capacity to remain composed and take a step back amid these outbursts. For instance, Munger stayed committed to long-term companies with actual profits and moats throughout the dot-com boom, while others invested billions in unproven startups. Although that constraint wasn’t always well-liked, it worked incredibly well when the market was down.

Munger’s impact extended beyond Berkshire through other significant endeavors. In his role as chairman of Wesco Financial, he oversaw a miniature Berkshire that followed the same business model as its parent corporation. He wrote legal journals at the Daily Journal Corporation that demonstrated his profound regard for ethics and the law, and he oversaw investments that produced noteworthy profits. He also served as a director at Costco, where he praised the company’s low prices and devoted client base with astute observations that held up well over decades of changing consumer preferences.

Munger also had a strong commitment to philanthropy and education. He made significant donations to academic institutions such as Stanford and the University of Michigan, frequently imposing design requirements to guarantee that students would benefit from well-thought-out areas. His design of dorms without windows in individual rooms—believing that natural light belongs in communal areas that promote human connection—was one of his favorite charitable endeavors. Although that unconventional idea sparked controversy, it emphasized his larger conviction that surroundings should be created to prioritize the common good over personal gratification.

CEOs, academics, investors, and regular people who had heeded his counsel poured forth accolades after his death in late 2023. In addition to being a millionaire, many saw him as a thinker whose reasoning had significantly enhanced their choices in both their personal and professional lives. In many respects, Munger’s methodical approach served as a counterbalance to the ostentatious, high-leverage, tech-driven stories that have dominated news headlines in recent years. His wealth was based on eternal principles—integrity, patience, and clear thinking—rather than upheaval.

Munger has been bluntly skeptical of topics including meme stocks, cryptocurrency speculation, and overpriced initial public offerings (IPOs) in recent years. His criticisms sprang from a deep-seated cynicism about anything that prioritized hype over substance rather than a fear of change. He referred to many well-known assets as “worthless delusions” and cautioned against the attraction of tales unrelated to earnings. Even if it was divisive, investors seeking unadulterated information appreciated such candor.

His lessons will probably continue to be essential reading for entrepreneurs, investors, and business executives in the years to come as they attempt to negotiate ever-more-volatile economic environments. Even in technologically accelerated situations, his mental models, emphasis on transdisciplinary thinking, and laser-like concentration on risk avoidance continue to be extremely effective. For individuals who prioritize long-term worth over short-term profits, Munger’s ideas could provide a soothing framework as artificial intelligence transforms business and finance.